Non-bank financial intermediaries (NBFIs) have surpassed banks as the largest global financial intermediaries. And yet, most NBFIs continue to be lightly regulated relative to banks for safety and soundness, whether in terms of capital and liquidity requirements, supervisory oversight, or resolution planning. Figure 1 shows, using data from the Financial Stability Board (FSB), that the global financial assets of NBFIs have grown faster than those of banks since 2012, to about $239 trillion and $183 trillion in 2021, respectively. In percentage terms, the share of the NBFI sector has grown from about 44% in 2012 to about 49% as of 2021, while banks’ share has shrunk from about 45% to about 38% over the same period.

Figure 1 Global financial assets of non-bank financial intermediaries and bank sectors, 2002-2021

Notes: The NBFI sector includes all financial institutions that are not central banks, banks, or public financial institutions. Included are all 19 Euro area countries, Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Cayman Islands, Chile, China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Africa, Switzerland, Türkiye, United Kingdom, and the United States. Source: Financial Stability Board [FSB] (2022).

The parallel, substitution, and transformation views of non-bank financial intermediaries and banks

One justification for the lighter touch of NBFI regulation, despite the sector’s prominence, is the view that banks and NBFIs pursue different or parallel intermediation activities. In particular, banks focus on deposits, loans, and payments, while NBFIs focus on capital markets. In this view, then, banks have to be heavily regulated to protect depositors and the real economy, while NBFIs can be lightly regulated and allowed to fail.

This parallel view of NBFIs and banks has influenced financial regulation in the US for at least 160 years, with banks being heavily regulated but restricted in the scope of their activities. The National Bank Acts of the 1860s prohibited national banks from many businesses, including trust activities, real estate lending, securities underwriting, and credit guarantees (Calomiris 2020). The Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 renewed the attempt to exclude commercial banks from underwriting securities. And the Volcker Rule, part of the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 (DFA), severely restricts bank participation in certain investment vehicles, and limits proprietary trading at banks to government securities and corporate loans (Richardson and Tuckman 2017).

However, the parallel view of NBFI and bank activity, along with the regulatory conclusion that NBFIs should be allowed to fail, does not square easily with the de facto official support of NBFIs, most notably during the Global Crisis but more recently as well. Instances include the Federal Reserve’s interventions in the repo markets in 2019 and through the COVID pandemic and shutdowns (Duffie 2020, Schrimpf et al. 2020), the Bank of England’s support of the gilt market in response to the liquidity problems of UK pension funds in 2022, and European governments’ protection of energy producers and derivatives users, also in 2022. The dissonance of the parallel view with the realities of NBFI rescues is reflected in how the Federal Reserve’s 13(3) powers to lend to NBFIs were changed by the Dodd-Frank Act, namely, to raise the procedural hurdles to such lending and to prohibit such lending to individual NBFIs, but, in the final analysis, to leave these broad powers in place.

A key challenge to policy based on the parallel view of the NBFI and bank sectors can be expressed in terms of a corollary of Goodhart’s Law (Goodhart 1975):

As the banking perimeter is used for “control” (regulatory) purposes, but activity around the perimeter can be “manipulated” (via regulatory arbitrage) by banks and NBFIs, the regulatory perimeter inexorably ceases to be useful for control purposes.

Put differently, the NBFI and bank sectors do not exist in parallel but are actually substitutes in that business lines and intermediation activities flow over time from banks to NBFIs at least in part because of relatively burdensome bank regulation. Furthermore, in this substitution view, NBFIs take on intermediation roles, in kind and volume, that can be systemically important and can lead to rescues by authorities in times of financial stress.

The substitution view of the NBFI and bank sectors, along with the implication that NBFIs can become systemically important, is very much consistent with the powers given by the Dodd-Frank Act both i) to the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) to designate NBFIs as systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs) and to regulate them accordingly, and ii) to the United States Treasury and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation to resolve a failing large and complex financial company. Metrick and Tarullo (2022) recommend dealing with the substitution problem through a ‘congruence principle’, through which similar activities are regulated similarly, whether those activities are pursued within NBFIs or banks.

In Acharya et al. (2024), we take a different view of the NBFI and bank sectors, arguing that neither the parallel nor substitution views adequately describe how activities align across these sectors. Instead, we posit that intermediation activities—including the types of claims held by each sector, the manner of their financing, and contingent liquidity arrangements—endogenously transform across sectors so as i) to loosen regulatory constraints and reduce regulatory costs across the financial sector as a whole, along the lines of Goodhart’s Law, and ii) to harness the inherent funding and liquidity advantages of bank deposit franchises (Kashyap et al. 2002) and access to safety nets (Gatev and Strahan 2006), whether explicitly in the form of deposit insurance and central bank lender of last resort (LOLR) financing or implicitly in the form of too-big-to-fail insurance. Our transformation view predicts that the intermediation activities and risks of NBFIs and banks become intricately intertwined, which is a result we demonstrate through a variety of cases and empirical analyses of recent developments.

More on the transformation view and its implications

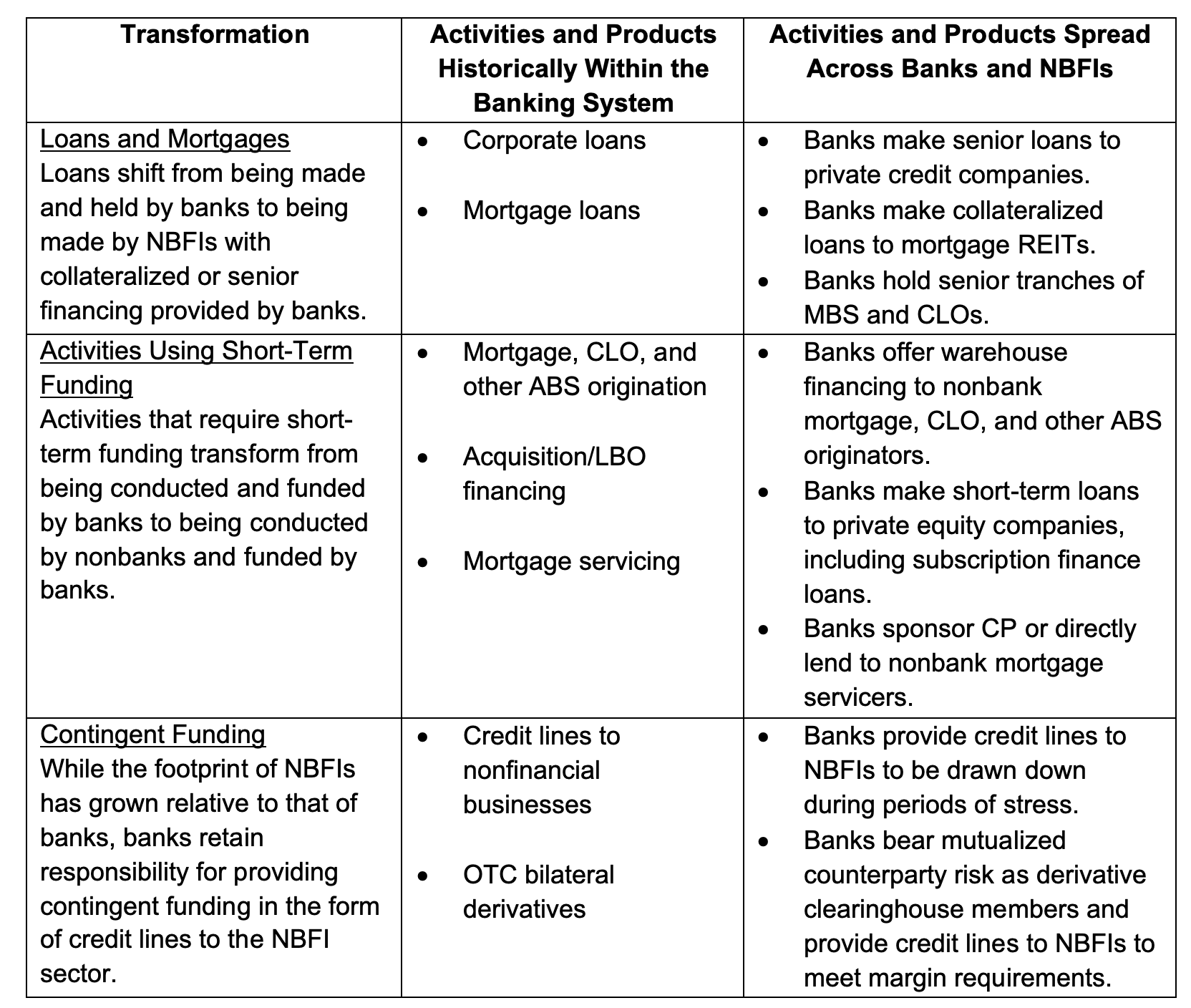

Table 1 gives examples of three categories of transformations that describe relatively recent trends in financial markets.

Table 1 Examples of transformations of intermediation activities across the non-bank financial intermediation and bank sectors

- Loans and mortgages: Through recent history, banks held corporate and mortgage loans and bore the associated interest rate and default risks. Over time, however, at least in part due to higher capital requirements and tighter regulations on leveraged lending, large volumes of these loans no longer reside on bank balance sheets. Instead, banks have retained indirect loan exposures through senior loans to private credit companies, collateralised loans to mortgage Real Estate Investment Trusts (mortgage REITs, or mREITs), and the generally more senior claims of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralised loan obligations (CLOs). Hence, risks of the underlying loans may seem to have left the banking system but have actually been transformed into more senior holdings of exposures to NBFIs.

- Activities using short-term funding: Traditionally, banks participated in various businesses that rely on regular or continuing short-term funding. Examples include the following: securitisation, in which the purchases of underlying assets are funded until they are securitised and sold as MBS (mortgage-backed securities), collateralised loan obligation (CLOs), or other ABS (asset-backed securities); financing acquisitions in general, and leveraged buyouts (LBOs) in particular, in which acquisitions are funded in anticipation of bond sales to investors; and mortgage servicing, which requires servicers to fund payments of delinquent amounts to mortgage-backed security investors until government insurance pays the related claims. These activities used to be dominated by banks but are now dominated by NBFIs. However, banks provide NBFIs with the short-term funding used to carry out these activities in the forms of direct loans, warehouse financing, credit lines, subscription finance loans,

and bank-sponsored (or credit-enhanced) commercial paper.

- Contingent funding: While the previous category includes the regular or continuing use of short-term funding, which can take the form of credit lines, this third category includes the provision of unusual or emergency short-term funding, or liquidity insurance, which is most often manifested in the drawing down of bank credit lines in unusually high volumes. Activities in this category are those in which NBFIs have replaced banks in financing or other activities but rely themselves on banks for the necessary contingent funding. In other words, the entirety of these activities is not a shift from banks to NBFIs, but a transformation in which regular or continuing financing shifts to NBFIs while unusual or emergency financing remains with banks. A relatively unheralded example is the post-Global Crisis mandate to clear most derivatives, like interest rate swaps (IRS), that had previously been bilateral and traded over-the-counter (OTC). This mandate has transformed the counterparty risk that banks faced as derivative counterparties of NBFIs to the liquidity risk banks face in providing credit lines to NBFIs to meet calls for additional initial and variation margin.

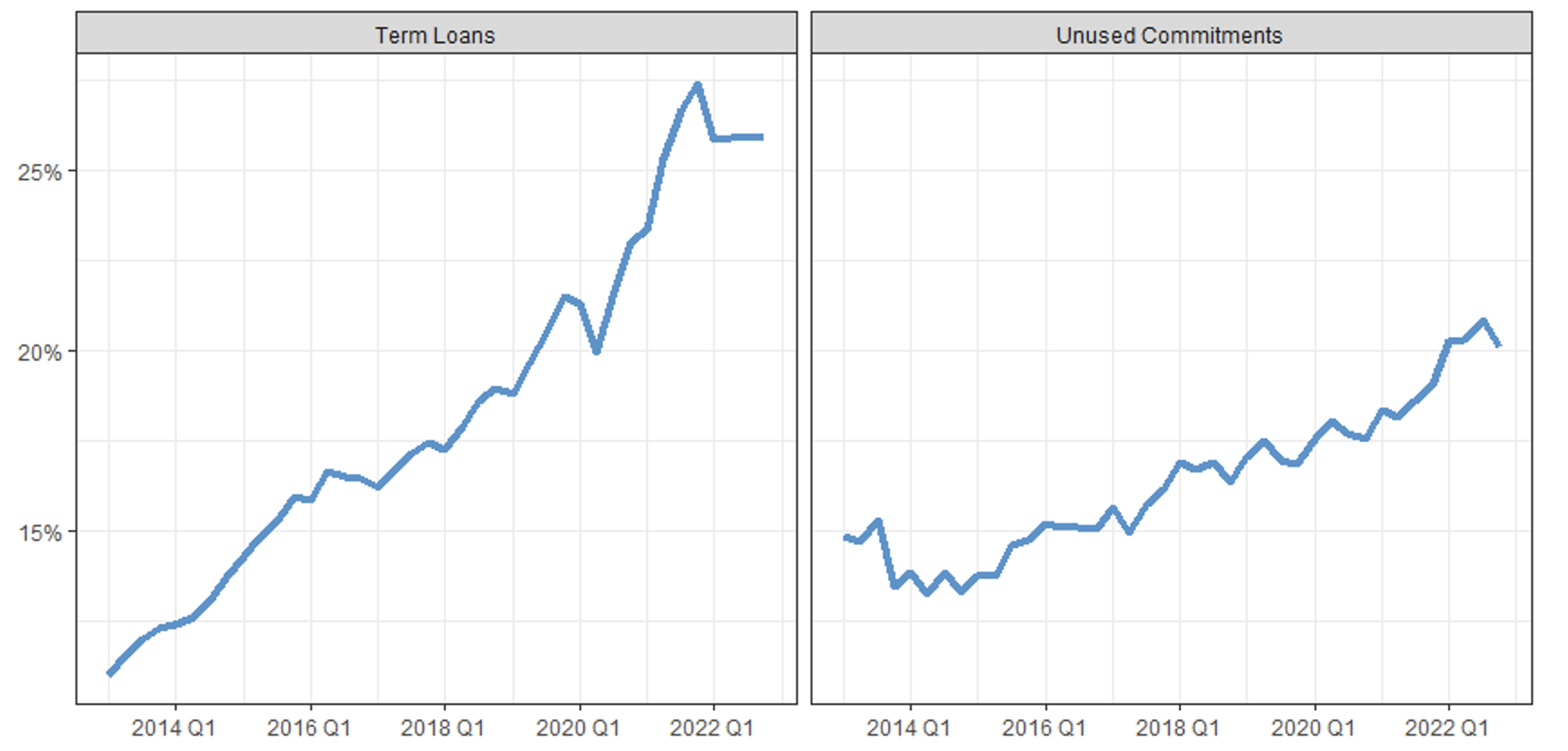

Figures 2, 3, and 4 show the importance of the first two transformations just described in terms of the increasing amounts of bank loans and credit commitments to NBFIs from 2013 to 2023.

Figure 2 Bank loans to non-bank financial intermediaries, by NBFI sector, 2013-2023

Notes: Term loans from US bank holding companies, US intermediate holding companies of foreign banking organisations, and savings and loans holding companies with $100 billion or more in total consolidated assets. Borrowers are grouped based on their business activities as identified by the North American Industry Classification (NAICS) code.

Source: Form FR Y-14Q, Schedule H.1.

Figure 2 depicts the growth of bank loans to NBFIs rising from about $125 billion to over $300 billion. The greatest growth was for bank loans to ‘Other Investment Pools and Funds’, which includes money market funds, mutual funds, mortgage REITS, issuers of asset-backed securities (including CLOs), business development companies (BDCs), and private credit funds. Figure 3 depicts the growth of bank credit line commitments to NBFIs rising from about $500 billion to over $1,500 billion, with the greatest growth again to Other Investment Pools and Funds. Figure 4 shows aggregate loans and credit commitments to NBFIs as a share of total bank loans and credit commitments. Hence, while Figures 2 and 3 show that funding of NBFIs by banks has increased in dollar terms, Figure 4 shows that this funding has also increased as a percentage of total bank funding.

Figure 3 Bank credit line commitments to non-bank financial intermediaries, by NBFI Sector, 2013-2023

Notes: Credit line commitments from US bank holding companies, US intermediate holding companies of foreign banking organisations, and savings and loans holding companies with $100 billion or more in total consolidated assets. Borrowers are grouped based on their business activities as identified by the North American Industry Classification (NAICS) code.

Source: Form FR Y-14Q, Schedule H.1.

Figure 4 Bank loans and credit line commitments to non-bank financial intermediaries as shares of total bank loans and credit line commitments, 2013-2023

Notes: Term loans and credit line commitments from U.S. bank holding companies, U.S. intermediate holding companies of foreign banking organizations, and savings and loans holding companies subject to consolidated financial statement reporting requirements.

Source: Form FR Y-9C.

While a definitive conclusion would require significantly more research, we believe that the transformations we document are driven at least in part by regulatory arbitrage and consequently could result in an inefficient allocation of activities and risks in the financial system. Accepting this premise, the post-Global Crisis tightening of bank regulation will likely overstate reductions in systemic risk. NBFIs and banks will jointly take more risk than socially optimal, including NBFIs demanding too much extraordinary liquidity from banks under stress. Authorities will consequently have to intervene more often than optimally to preserve the ecosystem of NBFI-bank intermediation, either by direct rescues of NBFIs or by indirect rescues through the banking system. Put another way, our analysis indicates a transformation of banking sector’s systemic risk to a nexus of NBFI-bank systemic risk.

Authors’ Note: The views expressed in this piece are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the Federal Reserve System, or any of their staff.

References

Acharya, V V, N Cetorelli and B Tuckman (2024), “Where Do Banks End and NBFIs Begin?”, NBER Working Paper 32316.

Calomiris, C (2020), “The Evolution of Bank Chartering”, Moments in History, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, 7 December.

Duffie, D (2020), “Still the World’s Safe Haven? Redesigning the U.S. Treasury Market After the COVID-19 Crisis”, Hutchins Center Working Paper #62.

Financial Stability Board [FSB] (2022), “Global Monitoring Report on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation”, 20 December.

Gatev, E and P Strahan (2006), “Banks' Advantage in Hedging Liquidity Risk: Theory and Evidence from the Commercial Paper Market”, Journal of Finance 61(2): 867-892.

Goodhart, C (1975), “Problems of Monetary Management: The U.K. Experience”, Papers in Monetary Economics 1: 1-20.

Kashyap, A, R Rajan and J Stein (2002), “Banks as Liquidity Providers: An Explanation for the Coexistence of Lending and Deposit‐taking”, Journal of Finance 57(1): 33-73.

Metrick, A and D Tarullo (2022), “Congruent Financial Regulation”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, January.

Richardson, M and B Tuckman (2017), “The Volcker Rule and Regulations of Scope”, in M Richardson, K Schoenholtz, B Tuckman and L White (eds.), Regulating Wall Street: Choice Act vs. Dodd Frank, NYU Stern School of Business.

Schrimpf, A, H Shin and V Sushko (2020), “Leverage and margin spirals in fixed income markets during the Covid-19 crisis”, BIS Bulletin No. 2, 2 April.